How To Beat Your Company’s “Batterygate”

How To Beat Your Company’s “Batterygate”

In this weekly series, I opine on how language and content affect the way we understand the products and services around us. I do this for your entertainment and education (and, of course, to remind you that if you’re looking for a freelance copy, content, product, or technical writer… yada yada, hire me).

After working in product and tech comms for 10 years, there’s still tons I don’t know. That said, I have learned a few things:

- A good product in market is better than a perfect product in development.

- No one knows the customer’s pain better than customers.

- Prospects (active and passive) are just as important as customers — if and only if you know how, and when, to listen to them.

- A feature list is not a roadmap.

- An exit is not a vision.

I could go on (and I probably will in another post at some point), but above all else, the lesson I’ve learned most painfully is that a product company is not smarter than its customers.

There are many reasons why this is true, but if you approach your business like this, you’re eventually going to have something blow up on you. And when it does, you’re going to fuck up your response to it. And you’re going to do so because you act from a place of feeling you’re smarter than your customers.

When you do? You end up, like Apple, with your own Batterygate.

Wait, What Happened?

Late last year, a fervor broke out on Reddit when evidence surfaced that seemed to confirm what many had long believed: Apple had built software to limit performance on older phones. It had planned obsolescence.

To get to the bottom of this issue, Primate Labs’ John Poole performed a deep analysis on the battery life of various iPhone models.

Sure enough, he validated what appeared to be true. Apple was throttling performance on old phones.

What Followed

Every blogger, critic, and mainstream new outlet jumped on the story. Tech companies are the new banks, after all, and villainy that simply could not stand was afoot.

Within 10 days, Apple conceeded with a (rare) formal apology about the matter.

The reality behind the hysteria is, as usual, more complex than the bubbling conspiracy suggested.

The lithium ion batteries employed in virtually every rechargeable device today have one fatal flaw (aside from exploding): they degrade over time. This is as true for Samsung phones as it is for Apple phones as it is for your crappy wireless speaker that you take to the beach. Eventually, all of our rechargable devices will be unable to hold a charge.

The Result

Unfortunately for Apple, because it had never addressed this issue with its consumers, and given its position as a market leadaer, the company was left open to the absolute assault on it that followed the story’s break.

Apple had to make a number of major corrective actions:

- It lowered the price of its battery replacement program (which is already a lot more generous and easy to make use of than similar programs from other smartphone providers)

- It published a slab of content detailing how to maximize battery performance, direct from its brand (as opposed to via Support)

- It committed to investing further R&D dollars towards improving the way that iOS exposes, and allows for configuration of, its battery management features.

In spite of these actions, the company almost immediately came under formal investigation by a number of governments alongside its major rival Samsung,

In parallel, it failed to stem the tide of negative consumer sentiment which rivaled Antennagate — and at a time when the competition has been poking at Apple’s approach to battery tech pretty visibly.

The Takeaway

You might argue that Apple took the brunt of the battery blowback simply because it’s “the biggest brand”.

Sure, Apple has been trying to ignore the whole planned obselence thing for years (the iPod was a famous perpetrator, as an example), and even had a major previous “batterygate” event in 2011.

Yet, it has never before been hit so hard, so fast, with so much fervor about the issue, and that’s why I believe Apple could have avoided this.

How Apple Failed

Apple’s big failure here was rooted, perhaps ironically, in the same behaviour that has made it successful in its product marketing and advertising efforts previously.

Apple’s go-to-market approach is aimed towards, and predominantly messages to, a consumer-base that it considers largely uneducated about tech.

Indeed, somewhere buried within a Keynote presentation at the Cupertino campus exists a group of personas ranging from the “average preteen in middle America” to the “New York Wall Street hedgefund manager”.

The tie that binds these personas? A fundamental belief (born from Apple’s understanding of user pain) that their device “should just work”, with the underlying assumptive corrollary of “…and I don’t care how it does”.

But that deck must be dated 2010, stagnant and unrepresentative of the market now shifted — and that corrollary is where the issue stems.

As the prices of personal technology have climbed, so too has consumers’ general, literal, and emotional investment in the devices that line their person.

As phones have gotten faster, thinner, bigger, lighter, only one major area of innovation remains largely untapped: the battery. Batteries haven’t gotten much better, and our expectations of battery life reflect that.

We’ve all felt the pang of the red battery icon. And that’s a pain that Apple missed on its lean canvases. That’s why batterygate is so triggering.

The idea that Apple is not only not solving for but rather actively hindering the lifespan of a phone’s battery is something any consumer will have a kneejerk reaction to, and understandably at that.

So, how could this have been avoided?

What Would PMM Do

There’s a well-worn idiom in the world of product development for when something goes wrong in a somewhat useful way: we like to say “it’s not a bug; it’s a feature”.

I’ve always considered that statement to be a perfect example of why product marketing is so important: it’s all in how you position your features.

Apple chose a very deliberate positioning for battery management in iOS, particularly in the last few releases: it deemed the topic too “unsexy” to discuss or build around. Wireless charging is way cooler and a more “sellable” problem to the battery issue, the company thought.

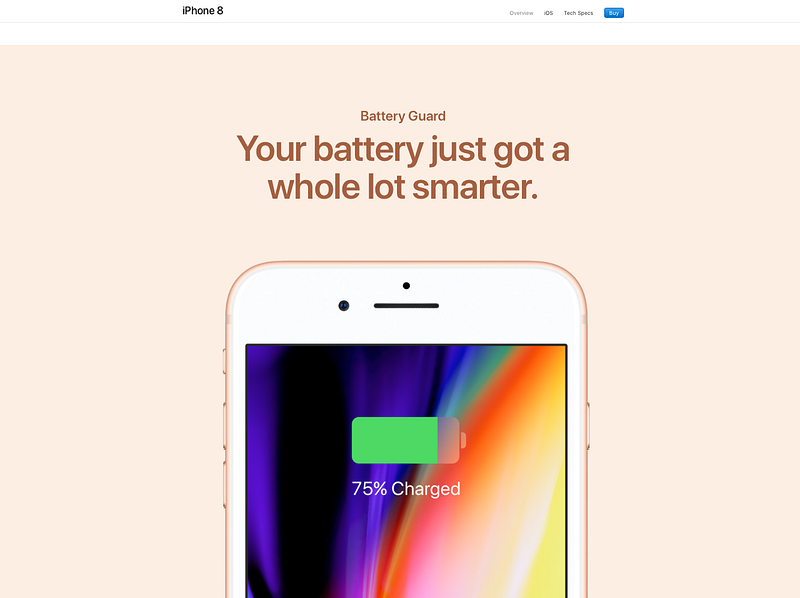

But with an understanding for a user’s pain (“my battery sucks and as my phone gets older, it keeps randomly dying on me”) and with respect for a user’s interest in the matter (as well as their high-level understanding of the tech in their phone), the company’s go-to-market for its new battery tech should’ve looked more like this:

By working the battery tech into a “feature”, rather than having it manifest to user as a “bug”, the company could have shaped the story from the get-go. People would have been aware of, and expecting, those new capabilities.

Would they have still been critical about them? Absolutely. But the mea culpa from “it doesn’t work quite as we’d hoped” is a patch, not a PR campaign.

In Apple’s underestimation of its consumer base, and what they find important, Apple created a huge problem that a little bit of smart product marketing on a website could’ve solved — for far less money.

TL;DR

Know your audience, know their pains, and don’t underestimate them. The more you try to hide, the more likely your attempt to outsmart your customer will come back to bite you.

What about you? Any lessons you’ve drawn from this? Respond away. And if you’d like to learn more about me or my business, visit www.frankcaron.com.